Austral Comunicación

ISSN(l) 2313-9129

ISSN(e) 2313-9137

e01504

Sociocultural factors in the spread of environmental misinformation

Evidence from Arauco Province, Chile

Nicole Villagra

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-2620-0892

Concepción, Chile

Oscar Basulto

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8323-1098

Concepción, Chile

Ignacio Riffo-Pavón

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6691-3572

Santiago de Chile, Chile

Fecha de finalización: 30 de enero de 2025.

Recibido: 2 de febrero de 2025.

Aceptado: 6 de noviembre de 2025.

Publicado: 27 de noviembre de 2025.

DOI: https://doi.org/26422/aucom.2026.1501.vil

![]()

Abstract

In light of the growing environmental challenges facing societies and the rise of misinformation, which is becoming a significant threat to informed decision-making and effective environmental action, this study investigates the correlation between sociocultural variables and the inclination to believe and share misinformation related to the environment. A survey was conducted among 334 adults residing in the Province of Arauco, located in south-central Chile. The study analyzes the data using Spearman correlation tests and ANOVA. The findings reveal that, in general, there is no significant correlation between sociocultural variables (generation, gender, educational level, ideology, and religion) and attitudes toward believing and sharing fake environmental news. In particular, a weak negative correlation was found between generation and the willingness to believe and share misinformation suggesting that older generations may exhibit lower susceptibility. Furthermore, politically engaged individuals showed a weak negative relationship, indicating a greater likelihood that political ideology influences the acceptance of misinformation. The results also highlight the underlying problem of people struggling to differentiate between true and false information, with a high percentage (83%) of participants failing to accurately identify the misinformation presented.

Keywords: attitudes; belief; environment; misinformation; sharing.

Factores socioculturales en la difusión de desinformación ambiental

Evidencia de la Provincia de Arauco, Chile

Resumen

Ante los crecientes desafíos ambientales que enfrentan las sociedades y el auge de noticias falsas que se convierten en una amenaza significativa para la toma de decisiones informadas y la acción ambiental efectiva, este estudio investiga la correlación entre variables socioculturales y la inclinación a creer y compartir noticias falsas relacionadas con el medio ambiente. Se realizó una encuesta entre 334 adultos residentes en la provincia de Arauco, ubicada en el centro-sur de Chile. El estudio analiza los datos mediante pruebas de correlación de Spearman y ANOVA. Los hallazgos revelan que, en general, no existe una correlación significativa entre las variables socioculturales (generación, género, nivel educativo, ideología y religión) y las actitudes hacia creer y compartir noticias ambientales falsas. En particular, se encontró una correlación negativa débil entre la generación y la disposición a creer y compartir desinformación, lo que sugiere que las generaciones mayores pueden exhibir una menor susceptibilidad. Además, las personas políticamente comprometidas mostraron una relación negativa débil, lo que indica una mayor probabilidad de que la ideología política influya en la aceptación de la información errónea. Los resultados también resaltan el problema subyacente de las personas que luchan por diferenciar entre información verdadera y falsa, con un alto porcentaje (83%) de participantes que no logran identificar con precisión las noticias con desinformación.

Palabras clave: actitudes; creencia; medioambiente; desinformación; compartir.

Fatores socioculturais na difusão da desinformação ambiental

Evidências da Província de Arauco, Chile

Resumo

Diante dos crescentes desafios ambientais enfrentados pelas sociedades e do aumento das notícias falsas que se tornam uma ameaça significativa para a tomada de decisões informadas e para a ação ambiental efetiva, este estudo investiga a correlação entre variáveis socioculturais e a inclinação para acreditar e compartilhar notícias falsas relacionadas ao meio ambiente. Foi realizada uma pesquisa com 334 adultos residentes na província de Arauco, localizada no centro-sul do Chile. O estudo analisa os dados por meio de testes de correlação de Spearman e ANOVA. Os resultados revelam que, em geral, não existe uma correlação significativa entre as variáveis socioculturais (geração, gênero, nível educacional, ideologia e religião) e as atitudes em relação a acreditar e compartilhar notícias ambientais falsas. Em particular, foi encontrada uma correlação negativa fraca entre a geração e a disposição para acreditar e compartilhar desinformação, o que sugere que as gerações mais velhas podem apresentar menor suscetibilidade. Além disso, indivíduos politicamente engajados mostraram uma relação negativa fraca, indicando uma maior probabilidade de que a ideologia política influencie a aceitação de informações incorretas. Os resultados também destacam o problema subjacente das pessoas que têm dificuldade em diferenciar entre informações verdadeiras e falsas, com uma alta porcentagem (83%) de participantes que não conseguem identificar com precisão as notícias com desinformação.

Palavras chave: atitudes; crença; ambiente; desinformação; compartilhar.

Introduction

Misinformation is an increasingly significant problem in today's society. Particularly when it comes to misinformation about the environment, its effects can be especially harmful to society, the planet, and even the long-term survival of the human species. Despite this, a review of the literature shows that previous studies have mainly focused on politics and health, making it necessary to understand the variables that influence belief in and dissemination of misinformation about the environment in order to develop more effective public policies.

Misinformation/fake news possesses three characteristics: its content is mostly false but is based on a true fact or detail; it is created with the intention of deceiving the audience in order to change an opinion or behavior in a way that benefits often undisclosed interests (Tandoc et al., 2018); and it imitates the format of journalistic news, which provides legitimacy for the reader (Mustafaraj & Metaxas, 2017). While polarization and misinformation/fake news have been identified as one of the main threats to democracy in Latin America, with recent examples cited in Brazil, Argentina, and El Salvador of politicians using disinformation as a political tool (Halpern et al., 2019; Valenzuela et al., 2021; Sahd et al., 2022), most previous studies on the subject have been conducted in Europe and the United States, focusing on analyzing the factors that influence users' ability to recognize misinformation, their likelihood of trusting it, or their intention to interact with such content. In general, these studies identify three major groups of relevant variables: (1) message characteristics, (2) susceptibility to misinformation/fake news due to individual factors, and (3) interventions, such as warnings, that lead people to consider the truthfulness of the information (Bryanov & Vziatysheva, 2021).

Influential disinformation campaigns have manipulated scientific knowledge, sowed confusion among the population, and threatened environmental progress (Fake news threatens a climate literate world, 2017). Misinformation/fake news has been used to downplay the severity of environmental issues, promote harmful practices for the environment, and even discredit the overwhelming scientific consensus on man-made climate change, pushing the idea that there is significant scientific controversy on the subject (McIntyre, 2018). This hinders the adoption of effective measures, both at an individual and collective level, resulting in serious consequences for the environment and future generations.

This study examines the relationship between sociocultural variables and the inclination to believe and share misinformation about the environment. By examining these relationships, we aim to deepen our understanding of the complex influences on environmental disinformation and shed light on potential overlaps and disparities with other types of misinformation.

Material

The ABC of Attitudes

The ability to distinguish misinformation/fake news from real news, as well as people's attitudes towards it, has become a relevant research topic for both theory and practice (Bryanov & Vziatysheva, 2021). This research argues that individuals may develop negative attitudes towards misinformation if they are able to identify it, based on two models taken from the field of Social Psychology that explain how attitudes are composed and formed.

Over the years, various interpretations of the concept of attitude have been proposed in the social sciences. Some authors, such as Bolívar (1995), describe attitudes as factors that influence an acquired action or behavioral predisposition towards an object or situation. Morales (2000) defines attitudes as learned and stable predispositions, although capable of change, to react evaluatively to objects, individuals, groups, or situations. Briñol et al. (2007) define attitudes as global and relatively stable evaluations that people make about other people, ideas, or things, also known as objects of attitude. On the other hand, Vallerand (1994) identifies attitudes as an intangible construct that combines cognitive, affective, and conative aspects, motivating and directing action and exerting influence on perception and thought. Attitudes are acquired, persistent, and characterized by a simple evaluative dimension of pleasantness or unpleasantness.

Multiple authors (Allport, 1954; Judd & Johnson, 1984; Breckler, 1984; Chaiken & Stangor, 1987) have argued that every attitude includes three components: the cognitive, the affective, and the conative or behavioral components, which can also be understood as thinking, feeling, and doing verbs (Saleh & Kinaan, 2020). This study adopts two models that help understand these three components: the tripartite model (Rosenberg & Hovland, 1960) and the ABC model (Ellis, 1985).

For both models, the affective component refers to the emotional dimension of attitude; it relates to how people feel about a particular object or topic. This component can encompass a wide range of emotions, such as love, hate, joy, sadness, anger, among others. On the other hand, the behavioral component refers to the actions or behaviors that an individual may exhibit in relation to the object of the attitude. It refers to how the attitude influences a person's behavior. Finally, the cognitive component refers to the individual's beliefs and perceptions about the object of the attitude. This component may include an individual's knowledge, opinions, and values regarding the object (Breckler, 1984). It is important to clarify that when this study refers to “belief” as part of the cognitive component of attitude, it is understood as propositions that are considered true by an individual and serve as a basis for their behavior (Wittgenstein, 1991). These beliefs may be based on direct experience, information received from others or the media, or on personal logic or reasoning.

Rosenberg and Hovland (1960) argue that the three components of attitude - cognitive, affective, and behavioral - are closely related and can mutually influence each other, affecting a person's attitude towards a particular topic. Ellis (1985) argues that a person's beliefs or thoughts about an event or situation can influence their emotional response or behavior towards it. Ellis (1985) proposes that there is a logical structure in how the three components - activating events that trigger an affective response (A), beliefs (B), and consequences or behaviors (C) - affect each other.

Method

This study explores sociocultural factors in attitudes toward environmental misinformation. It examines political ideology, religious identity, and demographics to understand their influence on perceiving misinformation as credible and sharing it. Based on attitude models, it proposes that certain groups or characteristics may lead to perceiving and sharing misinformation. Additionally, the study investigates how affective and cognitive components influence behavioral intentions. All the above leads to around the following hypotheses:

H1: With increasing age, belief in and sharing of environmental misinformation will decrease.

H2: Certain genders will have a higher tendency to believe and share environmental misinformation.

H3: Left-leaning political affiliations will be associated with lower belief in and sharing of environmental misinformation.

H4: Practicing a religion will be associated with higher belief in and sharing of environmental misinformation.

H5: Higher educational levels will be associated with lower belief in and sharing of environmental misinformation.

Sample Analysis

To delimit the results, the study was restricted to the Arauco Province in Chile, a region known for its high industrial activity, levels of poverty, and low quality of life. This situation is largely due to the historical relationship that the region has maintained with the forestry industry, which nationally contributes 3% to the country's Gross Domestic Product (Bolados et al., 2021; Banco Central de Chile, 2022). This tense relationship between the industry and the local community makes the Arauco Province particularly prone to the dissemination of misinformation related to the environment.

The sample was determined using the statistical formula for infinite populations, considering a confidence level of 95.5%, a margin of error of 2.5%, and an unknown variance. The ideal sample size was 1600, which would have been statistically representative, but, due to the limited timeframe available for data collection—restricted to a two-month period (October and November 2022)—it was not feasible to survey the entire population. To ensure the study could be completed within this window while still obtaining representative insights, it was decided to work with a sample equivalent to 10% of the population (N=160). Data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire on the Google Forms platform, which allowed for efficient reach and timely responses under the given constraints. To address potential concerns about representativeness in an online survey, recruitment was carried out through multiple channels (e.g., municipal offices, community organizations, schools, and neighborhood networks) to reach participants with varying levels of internet access. In addition, quotas were established based on key demographic variables of the Arauco Province population (Villagra, 2025).

The study, therefore, does not rely on a statistically representative sample. However, it does provide a general overview based on the sample that responded to the instrument. For reasons related to the institution that sponsored the study, it was not possible to continue the online survey for a longer period.

Analytical Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The original research on which this study is based was reviewed and approved by multiple faculty members from the Faculty of Communications, History, and Social Sciences of the Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción. The instrument was designed by the researcher, tested in a pilot study conducted in person in September, and was also reviewed, commented on, and ultimately validated by Federico A. Subervi-Vélez, an honorary member of the Program for Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The survey began with a section of practical application, where participants were presented with five news article headlines about the environment, four of which were true and one was fake, and were asked to answer a series of questions about their attitudes towards each one. In a second part, participants were asked to answer a dozen questions for sociocultural characterization.

Measurements

The three components of attitudes were measured using statements on a Likert scale. The affective component was measured with the statement: “I like this news”; the cognitive component with the statements: “This news confirms what I already knew” and “This news seems credible to me”; finally, for the behavioral component, four statements were used: “I would share this news with my close contacts,” “I would share this news on social media,” “The news seems credible to me, but I wouldn't share it,” and “The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it”.

On the other hand, the measured sociocultural variables were: Generation, where the participants had to indicate the year of their birth; Gender, requiring them to write their self-perceived identity; Educational level, asking them to indicate the highest level of education they had achieved at the time of answering the survey; Religion, where they had to indicate if they identified with any religion and their frequency of participation; finally, for ideology, they were asked to indicate their economic and moral position on two scales, with six options ranging from very right-wing to very left-wing. It is important to mention that for analysis purposes, the variables generation, gender, and ideology were recoded.

Results

Regarding the analysis plan, the initial sampling goal was set at 10% of the population, equivalent to 160 questionnaires. However, during the two-month fieldwork period, participation exceeded expectations, resulting in 338 completed questionnaires. This figure represents more than double the original target (211.25% of the required sample). During this process, four of them were discarded due to invalidity, as they did not meet the age requirements of the sample (they corresponded to individuals under 18 years old), thus leaving a total of 334 valid questionnaires to analyse. After processing these 334 surveys, the following descriptive statistics were obtained, which serve the purpose of characterizing the population of the Province that participated in the survey.

Statistics

The highest response rate was concentrated in the communes of Curanilahue, Cañete, and Arauco, which accounted for 61% of the respondents. Of the total respondents, sixty-six percent belong to the younger generations (Generation Z and Generation Y); however, no responses were recorded from the Silent Generation (born prior to 1945), which can be explained by the method used to disseminate the instrument, a self-administered online survey. Among the participants, 39% have completed secondary education, contrasting with the 2% who have no formal education. To conduct the surveys, information was provided through email databases and advertisements on digital platforms.

In addition, 35% identified as Catholic, 31% as Evangelical, and 31% as atheist or agnostic. The most common frequency of religious participation reported in the surveys is once every quarter, with 25% of the respondents indicating this frequency.

Regarding political aspects, 19% declared an interest in politics, another 19% indicated that it is a topic of occasional interest, and another 19% expressed no interest at all. In terms of values, 19% identified as fairly right-wing and 17% as fairly left-wing. In economic matters, 20% identified as fairly conservative and 18% as fairly liberal. The distribution of responses to this question preliminarily indicates a significant polarization in political spheres in the Province.

For News No. 1, which was true, the highest “strongly agree” option was expressed in the item “I like this news” (associated with the affective component), and “I find it credible” (associated with the cognitive component), both with a 63% acceptance rate. On the other hand, consistently, the highest degree of “strongly disagree” was recorded for the item: “The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it,” with 64% of people indicating agreement with this statement.

A similar pattern can be observed in News No. 2, also true, with a difference in the affective statement: 63% of respondents did not like this news, but the same percentage positively evaluated its credibility, and 83% indicated that this confirms their own beliefs to some degree or provides them with information they already knew.

In the case of News No. 3, which was manipulated to turn it into environmental misinformation, the figures are interesting. There were no “strongly disagree” responses regarding the affective item, with only 17% disagreeing with the statement “I like this news”. 82% of the respondents found it credible or very credible, while 17% strongly disagreed with this item. Furthermore, 82% stated that they would share it on social media, and 83% with their acquaintances. The manipulation of the news consisted of altering the written content and numerical data of the news.

For News No. 4, which was true, 67% identified a positive option in the affective component, while 9% strongly disagreed with the statement “I like this news.” However, 82% found the presented news credible. Nevertheless, this news only appeals to the confirmation bias of 41% of the respondents. An interesting fact is that while 83% would share this news with their acquaintances, only 9% would do so on their social media.

In the case of News No. 5, the figures differ significantly from the previous news, as the distribution is much more balanced among the four options, averaging a 25% preference for each in almost all questions. Only 43% of respondents found this news credible, while 42% stated they would share it with their acquaintances or on social media. However, 37% would share it despite not finding it credible.

When asked about the basis for their responses to the items regarding the presented news, the most chosen option was “only my knowledge,” closely followed by “only my opinion” and “the way the news is presented.” On the other hand, the option “cross-referencing sources” received an intermediate response, suggesting that some respondents use this technique. The option “reverse image search” was the least selected. However, this may be due to a lack of knowledge about these tools or how to use them, as they were not surveyed in this study. This raises questions for further research about individuals' reasoning when determining the authenticity of the information they encounter regarding environmental issues.

Correlations

In order to perform correlation analyses between the disposition to believe in and/or share fake environmental news and each of the five sociocultural variables, a scoring scale was established for attitudes based on the first six statements presented in the Likert Scale, where the maximum score is 21 points for each survey. For practical purposes, this score will be referred to as Set 1.

The seventh statement, which is directly related to the behavioural component of attitudes, was evaluated separately from the rest of the attitudes. For this, a scoring scale was also constructed that considers statements 1, 2, and 7, with a maximum score of 12; this will be referred to as Set 2.

Finally, statement number 7, “The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it”, was also evaluated separately. It is important to note that, in this way, attitudes are transformed into continuous numerical variables, which is relevant for data analysis.

Given that generation is a categorical variable, which means it represents a classification or categorization of individuals into specific groups, it is recommended to use non-parametric association tests instead of standard linear correlation tests (McDonald, 2014). In this case, the most appropriate test is the Spearman correlation coefficient (1904), which is used when variables have a non-normal distribution and are monotonically related, meaning that as one variable increases or decreases, the other does as well.

When crossing Generation with the attitude scoring scale, specifically regarding misinformation, it was found that there is a weak negative correlation between generation and the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in the Province of Arauco. The obtained values were r = -0.114 and p = 0.038. This means that for this specific population, as participants' generation increases, their willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation decreases. The p-value of 0.038 indicates that there is significant evidence to reject the null H. However, since the correlation coefficient is weak and only recorded for one news item (No. 5, a true news item), it is important to consider that this relationship is not very strong and other relevant factors may exist.

Similarly, when crossing Generation only with the statement “The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it,” a very similar result is highlighted, also for news item No. 5, with values of r = -0.117 and p = 0.032.

For Set 1, no significant values were recorded that could indicate a correlation.

In the case of gender, since it is a categorical variable with three different levels, the most appropriate analysis was ANOVA. This test is used to determine if more than two groups differ significantly in their means and variances (Hernández et al., 2014). Thus, the aim was to compare whether there are significant differences in the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation among the three gender groups.

Based on the results of this test, no significant evidence was found for a relationship between gender and the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in the Province of Arauco, both for the attitude score scale towards news (Set 1) and the attitude score scale towards misinformation (Set 2). The p-value in all cases is greater than 0.05, suggesting that, overall, gender does not appear to be a significant factor in the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in this Province.

One exception was found in the interaction between Gender and the statement “The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it,” where, in the case of News No. 2, significant evidence of a relationship between gender and the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in the Province of Arauco was found (F = 3.32, p = 0.037).

For the case of ideology, two analyses were conducted based on the collected data, using Spearman's correlation in both cases.

Firstly, the disposition to believe and/or share misinformation was cross-referenced with the variable “political interest,” reflected on a scale from 1 to 6, where 1 indicated no interest and 6 indicated very interested. In this case, weak negative evidence of a relationship was found for Set 1, specifically regarding News No. 3 with a correlation coefficient of -0.122 and a p-value of 0.026. The p-value being less than 0.05 suggests that participants with a higher level of political engagement may have a lower disposition to believe and/or share misinformation compared to those with a lower level of political engagement.

Secondly, these scales (Set 1 and Set 2) were cross-referenced with the ideology variable. This variable was constructed by averaging the responses to survey items 9 and 10, which represent self-identification on the value-based political spectrum and the economic political spectrum, respectively.

Based on the results of the Spearman's test, however, no significant evidence of a relationship between this factor and the disposition to believe and/or share misinformation was found among adults in the Province of Arauco. The p-values for all three data cross-references, including statement seven (“The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it”), were greater than 0.05.

Looking to examine whether there is a relationship between religion and the inclination to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in the Province of Arauco, we employed two types of statistical analysis. Firstly, a Spearman correlation was conducted to assess the possible relationship between the frequency of religious participation and the inclination to believe in and/or share misinformation. Secondly, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to examine whether significant differences exist in the inclination to believe in and/or share misinformation among different religions in the studied population.

Regarding the analysis to evaluate the relationship between the frequency of religious participation and the inclination to believe in and/or share misinformation, no significant values were found for any of the analyzed sets. This suggests that there is insufficient evidence to claim the existence of a statistically significant relationship between the variables.

Furthermore, the ANOVA analysis conducted to assess the relationship between religion and the inclination to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in the Province of Arauco yielded non-significant values, indicating that there is insufficient evidence to assert that the religion to which the respondents adhere plays a role in their attitudes towards misinformation.

After conducting the Spearman correlation, no significant values were found indicating a relationship between the educational level and the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation among adults in the Province of Arauco.

In this regard, a review of the literature revealed that previous studies have explored the relationship between educational level and the propensity to believe in and share misinformation. However, the results have been varied and do not allow for the determination of a clear correlation or causality between the variables. Some studies have found a positive correlation between educational level and the ability to identify misinformation, while others have found negative correlations. Therefore, in light of this research, it seems necessary to conduct further investigations to clarify this matter and obtain more conclusive results that clearly establish whether there is a relationship between educational level and the inclination to believe in and share misinformation, and if so, what its direction would be.

Discussion

The results obtained in the study, after analyzing the sociocultural variables and their relationship with the willingness to believe in and share fake environmental news among the adult population of the Province of Arauco, indicate that there is no significant correlation between the variables. However, despite not finding significant evidence of a clear relationship between them, there are some exceptions where weak correlations were observed, which require further studies and/or qualitative deepening to better understand them.

The generational factor

One of the exceptions found is the case of the generational variable, where a weak negative correlation was found between generation and the willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation, specifically for News Article No. 5. This suggests that as the generation of the participants increases, their willingness to believe in and/or share misinformation decreases. However, it is important to note that this relationship is not very strong and there may be other relevant factors. Nevertheless, this finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in other countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Jordan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Australia, among others (García & Casero, 2022).

In the literature, several possible explanations for this relationship can be found. One of the main explanations is that younger generations are exposed to social media and the information disseminated disseminated on it from an early age. At the same time, social media has been identified by various studies in Chile (Valenzuela et al., 2019; Montero & Halpern, 2019) and the world (Farooq, 2018; Talwar et al., 2019) as a means for the spread of misinformation and disinformation due to the ease with which messages can be shared and disseminated without proper fact-checking.

Another explanation is the association that some studies (Rozgonjuk, 2021; Li et al., 2022) establish between younger generations and the “fear of missing out” phenomenon, more commonly known as FoMO. This is a psychological phenomenon that describes the anxiety and stress that some people feel when they think they may be missing out on an interesting or important social experience that others are having at that moment. Social media can amplify this feeling, as users constantly see posts from other people who appear to be living exciting and fun experiences (Çetinkaya et al., 2021; Tandon et al., 2022). In the context of misinformation, younger generations may be more concerned about staying updated with the information shared on social media, fearing to miss out on something important or relevant to their daily lives. In this sense, they may be more susceptible to believing in and sharing misinformation that seems to have high informational or emotional value, without taking the necessary time to verify the accuracy of the information (Talwar et al., 2019). Additionally, the feeling of being “up to date” with the latest news and trends on social media can provide a sense of belonging and social validation (Ahmed, 2020), which can increase the desire to share news, even if the authenticity of the information has not been verified.

On the other hand, older generations may have greater trust in traditional news sources such as newspapers and television. This seems to be influenced, among other things, by something called “generational attachment,” a term from psychology that has been used in communication sciences to refer to the familiarity people develop as they grow up with certain technologies (Taipale et al., 2021). Therefore, older individuals may be less willing or able to adapt to new technologies due to factors such as cognitive decline, lack of access or exposure, or simply a preference for what is familiar. All of this could also affect their willingness to trust news circulating online.

Political Involvement

When crossing the attitude rating scales towards news with the variable ideology, a weak negative relationship was found between interest in political issues and the willingness to believe and/or share misinformation, specifically regarding News No. 3, which was the only misinformation. This could suggest that more politically engaged individuals may be less prone to believing and sharing misinformation. This finding is consistent with previous research that has suggested that political beliefs and attitudes can influence the likelihood of individuals believing and sharing misinformation, where participation and involvement are relevant factors (Valenzuela et al., 2019; Calvillo et al., 2021).

Although multiple English-speaking studies establish a link between the willingness to believe or share misinformation and a conservative or right-wing ideology (Guess et al., 2019; Baptista et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2023), the results of this research did not find significant evidence of a clear relationship between self-perceived ideology (recategorized based on the scale present in the questionnaire as left, center, or right) and the willingness to believe and/or share misinformation. However, if we rely on the literature review conducted in Chapter II, it cannot be ruled out that other relevant factors, not considered in this research, exist, such as political polarization (Baptista et al., 2021) or belief in conspiracy theories (Anthony & Moulding, 2018; Van der Linden, 2020; Forster et al., 2021) that often propagate in political circles.

Other reasons that could help explain or better understand any of these three weak correlations include the desire to share information that aligns with one's beliefs and values (Sanz & Carro, 2019; Corbu et al., 2020), the search for attention and social validation on social media (Thompson et al., 2019; Apuke & Omar, 2020), lack of media literacy (Pérez et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2023), and lack of tools to verify the authenticity of news (Balakrishnan et al., 2021).

The Underlying Problem

|

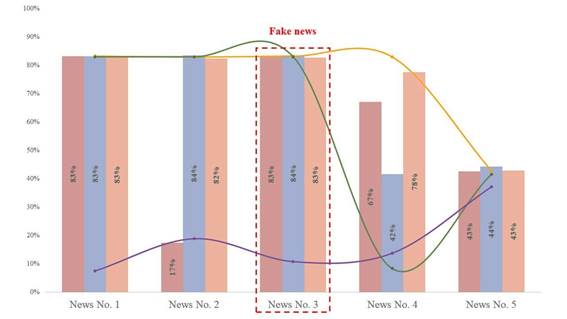

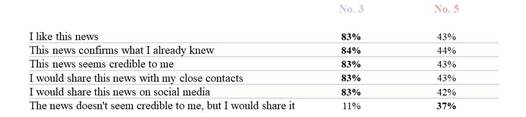

Based on the aforementioned, it is possible to state that this research confirms the conclusions reached by previous studies, already reviewed in this paper, which suggest that individuals, in general, face difficulties in distinguishing between true and false news information. According to these results, 83% of the study participants were unable to detect the presented misinformation, slightly surpassing the 70% obtained in an analysis carried out by Kaspersky in 2020 (Diazgranados, 2020). Specifically, News No. 3, titled “Fiscalía abre causa contra Arauco por floración de algas en el Golfo de Arauco” (“Prosecution opens case against ARAUCO due to algae bloom in the Gulf of Arauco”), which was false, was considered credible by 83% of the participants, while News No. 5 titled “NASA shoots laser beams at trees from the Space Station,” which was true, was mostly identified as false, with only a 43% accuracy rate (Figure 1).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Summary of news performance by attitude component.

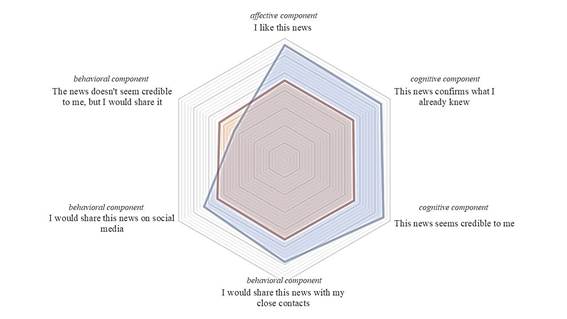

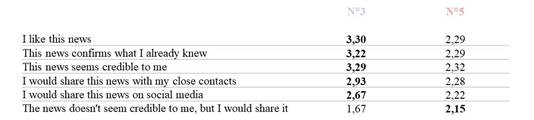

If we consider news No. 3 and No. 5, it can be observed that, despite news No. 3 being fake, it generated a more positive response overall when compared to news No. 5. The analysis of the averages of the three components of attitudes (affective, cognitive, and behavioral) for each news item shows that news No. 3 performed better. In terms of the affective component, news No. 3 had a higher average than news No. 5 (3.30 versus 2.29 points out of a possible maximum possible score of 4). Furthermore, news No. 3 outperformed No. 5 in the items of the cognitive component, with a difference of approximately one point. On the other hand, in the behavioral component, news No. 3 only performed better in the first two items, while in the third item, “The news doesn't seem credible to me, but I would share it,” news No. 5, which was true, obtained a higher average than news No. 3 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Performance comparison between News No. 3 and No. 5

according to attitude component.

Figure 2. Performance comparison between News No. 3 and No. 5

according to attitude component.

This result may be due to various factors. Firstly, the selected news articles. Despite being real, News Article No. 5 contains information that is surprising or difficult to believe for the reader, whereas News Article No. 3 was conceived in a plausible manner, with elements that make it appear authentic, fulfilling the characteristics outlined at the beginning of this research based on the existing literature on the subject (Mustafaraj & Metaxas, 2017; Tandoc et al., 2018).

The result obtained in this research can be explained by different factors. Firstly, the selection of the news articles must be considered. News Article No. 5, although truthful, contains information that may be shocking or hard to believe for the reader. On the other hand, News Article No. 3 fulfills the characteristics of an authentic news article, as described in the existing literature on the topic, by presenting plausible elements. The influence of the availability bias, which leads us to make decisions based on information that is more easily accessible in our minds, may have affected the results. In this sense, the mention of the possibility of “shooting laser beams from space” may have been immediately associated with concepts such as technology, futurism, and weapons, which are fundamental in popular science fiction movies and series, such as Star Wars, Star Trek, and Avatar. According to Box Office Mojo, a website that tracks box office revenues, there have been 27 extremely successful science fiction movies in terms of box office earnings in the last decade.

Furthermore, News Article No. 1, titled “Comunidades Mapuche en Arauco ingresan reclamaciones al SEA por proyectos eólicos en territorio ancestral” (“Mapuche communities in Arauco file complaints with the SEA regarding wind projects on ancestral territory”), follows a very similar pattern to No. 3, while News Article No. 2, “Pine and eucalyptus forest plantations affect water supply in large watersheds, study indicates”, generates negative feelings but confirms a pre-existing belief, which would explain why respondents show a willingness to share it regardless.

The case of News Article No. 4, titled “Investigadores de UNESCO demuestran que bosques y plantaciones forestales han frenado la desertificación en Chile” (“Unesco researchers demonstrate that forests and forest plantations have halted desertification in Chile”) is somewhat different. Although the news article generates mainly positive feelings, these numbers are not replicated in the following item associated with confirmation biases; it is new information that challenges people's pre-existing beliefs. However, by identifying it as “credible,” they are willing to share it with their close contacts, but not on their social networks.

This could find its origin in the phenomenon of “filter bubbles,” as individuals may feel insecure about sharing this information with their social media contacts for fear of being judged for going against what is considered popular or politically correct in their online social environment. Particularly in the Arauco Province, as well as in other sectors where forestry is the main industry, there is a rather negative perception of its presence in the area and its impacts (Florín, 2019).

Although no statistical evidence was found to support the various hypotheses regarding the influence of sociocultural variables and the willingness to believe and share environmental misinformation, the research has significant implications for the field of communication and environmental education by suggesting that cognitive and media literacy factors may play a crucial role in shaping people's beliefs and behaviors regarding environmental issues. Therefore, digital education that includes fact-checking and the promotion of critical thinking skills is necessary to prevent the spread of misinformation.

Limitations and Projections

Firstly, this study was based solely on a 26% sample of the population of Arauco Province in Chile. This means that the results obtained in this study are not generalizable to other populations, and additional studies with larger and more representative samples from other regions of the country would be needed to confirm these results.

Another important limitation of this study is the specific topic that was addressed: misinformation about the environment. Although this topic is relevant and current, the results obtained are limited to this particular topic and cannot be generalized to other areas such as politics, health, or economics, for example.

Thirdly, there is the possibility of inadvertent biases from the participants. Despite measures being taken to avoid biases and the use of rigorous methodology, since the application was not in person, some participants may have responded inaccurately or deceptively, which could have affected the results. Additionally, the lack of direct interaction with the participants may have also limited the opportunity to clarify any questions or misunderstandings they may have had.

And finally, in that same line, the use of an online questionnaire may have limited the participation of individuals who are not particularly adept at technology or who do not have internet access, which could have introduced bias in the sample selection.

However, based on the results obtained in this study, some recommendations for future research can be suggested. Firstly, it would be beneficial to broaden the topics addressed regarding misinformation, in order to assess how attitudes and behaviours towards misinformation vary in different contexts and subjects. This line of research would allow determining if the results found in this study are specific to environmental misinformation or if they apply to other topics, as well as identifying the differences and similarities among them.

On the other hand, the phenomenon could be explored from an interpretative paradigm, focusing on understanding the meaning individuals attribute to misinformation and how this relates to their social, cultural, and political experiences, worldview, and social identity. For this purpose, techniques such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and content analysis of environmental misinformation shared on social media and other communication channels could be employed. Similarly, it is suggested to delve into the research on participants' inadvertent biases in order to better understand how these biases can influence the perception of news veracity. For example, an analysis could be conducted on how political, religious, or social prejudices influence how people assess the credibility of news.

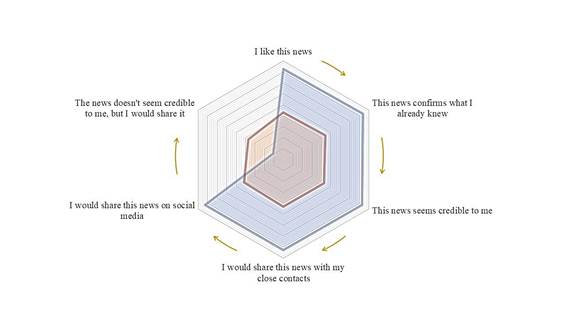

Finally, a topic that has been little explored is the study of misinformation from a psychological perspective, focusing on the effect of dopamine in the brain and how it can influence the reception and spread of misinformation. Specifically, regarding how individuals perceive and process information, and how this can affect their willingness to share misinformation they believe to be true or even misinformation they know to be false. For example, in this study, the specific analysis of News No. 3 (false) and News No. 5 (true) allows for theorizing about a possible cycle associated with dopamine release. News NO. 3 generated a significantly greater emotional response than News No. 5. The emotional response to News No. 3 was related to the generation of positive feelings that in turn activate dopamine release in the brain, according to literature and previous studies in the field of clinical psychology. Additionally, a confirmation bias was observed, where respondents were more likely to believe statements that confirmed their previous knowledge or beliefs, which further increases dopamine release (Hertz, 2014). Previous studies suggest that this process could lead

to the acceptance of claims without sufficient evidence (Schmack et al., 2015). Dopamine release can also motivate respondents to share the news with others, whether through social media or in person, driven by the pursuit of that “like” or interaction (Krach, 2010). On the other hand, the emotional response to News No. 5 was significantly lower, which may lead to questioning its credibility and decrease the motivation to share it (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cycle of brain reward when liking, believing and sharing news.

Conclusion

In this study on attitudes towards fake environmental news in the Arauco Province, Chile, a complex relationship between sociocultural factors and the willingness to believe and share false information is observed. Although no significant correlations were found, the inability of 83% of participants to distinguish between true and false news highlights widespread vulnerability to misinformation, reinforcing the need to enhance media literacy through critical thinking skills, digital competencies, and stronger educational strategies aimed at promoting informed and responsible civic engagement.

The literature supports the trends identified in this study, such as the association between youth and a propensity to believe in misinformation, linked to the “fear of missing out” (Rozgonjuk, 2021; Li et al., 2022). Additionally, the connection between political interest and susceptibility to misinformation resonates with previous research (Valenzuela et al., 2019; Calvillo et al., 2021), emphasizing the importance of addressing both media literacy and critical understanding of political information.

The study's limitations, such as the non-representative sample and the specific focus on environmental news, warrant consideration. Future research could expand on misinformation topics and adopt interpretative paradigms to explore individual and contextual perceptions of misinformation.

The reference to dopamine as a potential underlying factor in the reception and spread of misinformation suggests an intriguing direction for future psychological research on misinformation. This approach could open new avenues to understand how biological and emotional factors contribute to the spread of misinformation, particularly by examining reward-seeking behaviors, emotional gratification, and the neurochemical mechanisms that shape individuals’ susceptibility to persuasive false narratives across digital platforms and everyday social interactions.

Ultimately, this study underscores the urgency of improving media and cognitive literacy, as well as the need for multidisciplinary approaches to address misinformation. Collaboration among experts in communication, psychology, and social sciences is essential to develop effective strategies that mitigate the impact of misinformation on society. This persistent challenge demands innovative and educational solutions that strengthen the population's ability to confront the onslaught of false information and make informed decisions in today's complex media landscape.

References

Ahmed, N. (2020). Perception of Fake News: A Survey of Post-Millennials. Journalism and Mass Communication 10(1), David Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.17265/2160-6579/2020.01.001

Allport, G. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice (4th ed.). Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

Anthony, A., & Moulding, R. (2019). Breaking the news: Belief in fake news and conspiracist beliefs. Australian Journal of Psychology, 71(2), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12233

Apuke, O., & Omar, B. (2020). User motivation in fake news sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic: an application of the uses and gratification theory. Online Information Review, 45(1), 220-239. https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-03-2020-0116

Balakrishnan, V., Kee, S., & Rahim, H. (2021). To share or not to share – The underlying motives of sharing fake news amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. Technology in Society, 66(C), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101676

Banco Central de Chile. (2022, December 21). Principales resultados al tercer trimestre de 2022, Bcentral. https://www.bcentral.cl/web/banco-central/areas/estadisticas/comercio-exterior-de-bienes

Baptista, J., Correia, E., Gradim, A., & Piñeiro, V. (2021). Partidismo: ¿el verdadero aliado de las fake news? Un análisis comparativo del efecto sobre la creencia y la divulgación. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 79, 23-47. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1509

Bolados, P., Morales, V., & Barraza, S. (2021). Historia de las Luchas por la Justicia Ambiental en las Zonas de Sacrificio en Chile. Historia Ambiental Latinoamericana y Caribeña, 11(3), 62–92. https://doi.org/10.32991/2237-2717.2021v11i3.p62-92

Bolívar, A. (1995). La Evaluación de valores y actitudes. Anaya.

Breckler, S. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1191–1205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1191

Briñol, P., Falces, C., & Becerra, A. (2007). Actitudes. In F. Morales, E. Gaviria, M. Moya & I. Cuadrado (Eds.), Psicología Social (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Bryanov, K., & Vziatysheva, V. (2021). Determinants of individuals’ belief in fake news: A scoping review determinants of belief in fake news. PLoS ONE, 16(6), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253717

Calvillo, D., García, R., Bertrand, K., & Mayers, T. (2021). Personality factors and self-reported political news consumption predict susceptibility to political fake news. Personality and Individual Differences, 174, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110666

Çetinkaya, A., Kirik, A., & Gündüz, U. (2021). Fear of Missing Out and Problematic Social Media Use: A Research Among University Students in Turkey. Academic Journal of Information Technology, 32(47), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.5824/ajite.2021.04.001.x

Chaiken, S., & Stangor, C. (1987). Attitudes and attitude change. In M. R. Rosenzweig & L. W. Porter (Eds.), Annual review of psychology, 38, 575–630.

Corbu, N., Oprea, D., Negrea, E., & Radu, L. (2020). They can’t fool me, but they can fool the others! Third person effect and fake news detection. European Journal of Communication, 35(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120903686

Diazgranados, H. (2020). Digital Iceberg: 70% de los latinoamericanos desconoce cómo detectar una fake news. Kaspersky. Disponible en: https://latam.kaspersky.com/blog/70-de-los-latinoamericanos-desconoce-como-detectar-una-fake-news/17015/

Ellis, A. (1985). Cognitive, affective and behavioral components of attitudes. In M.J. Mahoney & A. Freeman (Eds.), Cognition and Psychotherapy. Springer.

Farooq, G. (2018). Politics of Fake News: How WhatsApp Became a Potent Propaganda Tool in India. Media Watch, 9(1), 106-118. https://doi.org/10.15655/mw/2018/v9i1/49279

Florín, C. (2019) Plantaciones forestales en Tirúa: El incendio como expresión de conflicto socio-ecológico [Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Católica de Chile]. https://estudiosurbanos.uc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/TESIS-CFD.pdf

Forster, R., Monteiro, R., Filgueiras, A., & Avila, E. (2021). Fake News: ¿O Que É, Como Se Faz E Por Que Funciona? FapUNIFESP In SciELO Preprints https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.3294

García, M., & Casero, A. (2022). ¿Qué nos hace vulnerables frente las noticias falsas sobre la COVID-19? Una revisión crítica de los factores que condicionan la susceptibilidad a la desinformación. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 28(4). 789–801. https://doi.org/10.5209/esmp.82881

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

Gupta, M., Dennehy, D., Parra, C., Mäntymäki, M., & Dwivedi, Y. (2023). Fake news believability: The effects of political beliefs and espoused cultural values. Information & Management, 60(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2022.103745

Halpern, D., Valenzuela, S., Katz, J., & Miranda, J. (2019). From belief in conspiracy theories to trust in others: Which factors influence exposure, believing and sharing fake news. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 11578, 217–232. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4144746

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la Investigación. McGraw-Hill.

Hertz, N. (2014). Eyes Wide Open: How to Make Smart Decisions in a Confusing World. HarperCollins.

Judd, C., & Johnson, J. (1981). Attitudes, polarization, and diagnosticity: Exploring the effect of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(1). 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.1.26

Krach, S. (2010). The rewarding nature of social interactions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 4, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00022

Li, L., Niu, Z., Mei, S., & Griffiths, M. (2022). A network analysis approach to the relationship between fear of missing out (FoMO), smartphone addiction, and social networking site use among a sample of Chinese university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107086

McDonald, J. (2014). Handbook of Biological Statistics. Sparky House Publishing.

McIntyre, L. (2018). Post-truth. MIT Press.

Montero C., & Halpern, D. (2019). Factores que influyen en compartir noticias falsas de salud online. El Profesional de la Información, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.may.17

Morales, P. (2000). Medición de actitudes y educación: Construcción de escalas y problemas metodológicos. Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid.

Mustafaraj, E., & Metaxas, P. (2017). The Fake News Spreading Plague: Was it Preventable? WebSci ’17: ACM Web Science Conference. https://doi.org/10.1145/3091478.3091523

Fake news threatens a climate literate world (2017). Nature Communications, 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15460

Pérez, A., Pedrero, L., Rubio, J., & Jiménez, C. (2021). Fake News Reaching Young People on Social Networks: Distrust Challenging Media Literacy. Publications, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9020024

Rosenberg, M., & Hovland, C. (1960). Cognitive, affective and behavioral components of attitudes. En C.I. Hovland y M.J. Rosenberg (Eds.). Attitude organization and change: An analysis of consistency among attitude components. Yale University Press.

Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J., & Montag, C. (2021). Individual differences in Fear of Missing Out (FoMO): Age, gender, and the Big Five personality trait domains, facets, and items. Personality and Individual Differences, 171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110546

Sahd, J., Zovatto, D., & Rojas, D. (2022). Riesgo Político América Latina. Centro de Estudios Internacionales CEIUC. http://centroestudiosinternacionales.uc.cl/images/publicaciones/publicaciones-ceiuc/Riesgo-Politico-America-Latina-2022-_compressed.pdf

Saleh, L., & Kinaan, A. (2020). Entrepreneurship and Crowdfunding in Lebanon: ABC Model of Attitude. International Business Research, 14(1), 119. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v14n1p119

Sanz, R., & Carro, C. (2019). Susceptibilidad cognitiva a las falsas informaciones. Historia y Comunicación Social, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.5209/hics.66296

Schmack, K., Rössler, H., Sekutowicz, M., Brandl, E., Müller, D., Petrovic, P., & Sterzer, P. (2015). Linking unfounded beliefs to genetic dopamine availability. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00521

Spearman, C. (1904). The proof and measurement of association between two things. American Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 72-101. https://doi.org/10.2307/1412159

Taipale, S., Oinas, T., & Karhinen, J. (2021). Heterogeneity of traditional and digital media use among older adults: A six-country comparison. Technology in Society, 66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101642

Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Kaur, P., Zafar, N., & Alrasheedy, M. (2019). Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.026

Tandoc, E., Wei Lim, Z., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining “Fake News”: A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143

Tandon, A., Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., & Mäntymäki, M. (2022). Social media induced fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing: Behavioural, relational and psychological outcomes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121149

Thompson, N., Wang, X., & Daya, P. (2019). Determinants of News Sharing Behavior on Social Media. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 60(6), 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2019.1566803

Valenzuela, S., Bachmann, I., & Bargsted, M. (2019). The Personal Is the Political? What Do WhatsApp Users Share and How It Matters for News Knowledge, Polarization and Participation in Chile. Digital Journalism (9)2, 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1693904

Valenzuela, S., Halpern, D., Katz, J., & Miranda, J. (2019). The Paradox of Participation Versus Misinformation: Social Media, Political Engagement, and the Spread of Misinformation. Digital Journalism, 7(6), 802–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623701

Valenzuela, S., Halpern, D., & Araneda, F. (2021). A Downward Spiral? A Panel Study of Misinformation and Media Trust in Chile. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(2), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211025238

Vallerand, R. J. (1994). La motivation intrinseque et extrinseque en contexte naturel. In R. J. Vallerand y E. E. Thill (Eds.), Introduction à la Psychologie de la motivation. Etudes Vivantes.

Van Der Linden, S., & Roozenbeek, J. (2021). Psychological Inoculation Against Fake News. In R. Greifeneder, M. Jaffe, E. Newman, N, Schwarz (Eds), The Psychology of Fake News: accepting, sharing, and correcting misinformation, (pp. 147-169). Routledge.

Villagra, N. (2025). Sociocultural factors in the spread of environmental misinformation in the Arauco Province, Chile - 2022 [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17585146.

Wei, L., Gong, J., Xu, J., Abidin, N., & Apuke, O. (2023). Do social media literacy skills help in combating fake news spread? Modelling the moderating role of social media literacy skills in the relationship between rational choice factors and fake news sharing behaviour. Telematics and Informatics, 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101910

Wittgenstein, L. (1991). Sobre la certeza. Gedisa.

*Roles de autoría

Los autores declaran que participaron por igual de la elaboración del trabajo, aprobaron la versión final para publicar y son capaces de responder respecto de todos los aspectos del manuscrito. Manifiestan no tener conflicto de interés alguno.

Obra bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.